One of the most gratifying comments in response to the publication of Shakespeare and the Stuff of Life (Bloomsbury, 2016) is that it doesn’t “quite fit into the standard categories” (San Diego book review). A collaboration between researchers in the History department of the University of Birmingham and The Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, this edited book aims to showcase some of the early modern artefacts from the Trust’s extensive museum collection with interpretation inspired by recent research in material culture studies.

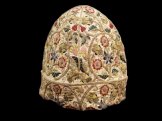

The book develops from almost a decade of knowledge exchange activities, including a blogging project ‘Shakespeare’s World in 100 Objects’, which treats a single object from SBT’s collection in each blog. The challenge for us in translating and channeling this team research and public engagement into a print publication was the issue of how to create a coherent narrative thread through which to examine in a sustained form a disparate group of material objects; items traditionally separated and classified by media in museum displays and publications (that is, by categories such as rare books, ceramics, metalwares, manuscripts, textiles, paintings, furniture, engraving etc).

Our solution was inspired by recent work on the relationship between material culture and the life cycle in early modern England. We had in mind, in particular, Nigel Llewellyn’s academic yet accessible book The Art of Death, published in 1991 to accompany an exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum and groundbreaking in its analysis of a wide-ranging but interconnected visual culture of death and remembrance. Since then, a good deal of scholarship has focused on the significance of crafted items in marking, negotiating and extending rites of passage in the life cycle such as birth, childhood, courtship, marriage and death.

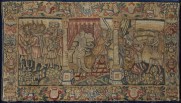

The life cycle in early modern England was understood as a series of phases, based on the ancient concept of the Ages of Man. Shakespeare engages directly with this tradition in Jaques’ ‘Seven Ages of Man’ speech from As You Like It. We therefore arranged our objects in groups to reflect these seven phases of life. This gave us the rationale through which to approach and interpret our selected objects; it proved remarkably easy to assign a phase of life to each of our objects, creating a sort of domino effect whereby interpretation of each object opened into the next, adding layers of meaning in the context of that particular phase of life, and moving the narrative on to the next. This is not, however, to suggest that understanding of these objects should be restricted to these themes and contexts; objects transcend fixed meaning and invite all kinds of personal reflection. As historians, however, we aim to make the mute and enigmatic material remains from the past explicable according to the social and cultural contexts that informed the circumstances of their making and use. The narrative of the life cycle seemed the most historically grounded and coherent interpretative apparatus through which to elucidate the significance of these items for Shakespeare and his contemporaries.

An example of the rich visual tradition on the ‘Ages of Man’ theme. A version of ‘The Staircase of the Ages’ by Cornelis Saftleven (1607-1681). University of Birmingham.

Reception to the book has been generally very positive, yet intriguingly quizzical. In straddling categories such as ‘Shakespeare’ and ‘Decorative Art’ or ‘Craft’ it has evidently proved difficult to label or characterise. There is a sense of mild bemusement around the immortal Bard’s connection with “cushion covers, bodices and oak cupboards” as well as with its public engagement agenda (described as one of the ‘cuter mementoes’ published to coincide with the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death in an overview in the Evening Standard).

Its multifarious nature and applicability to unexpected fields is borne out by its appearance on certain Amazon Bestsellers lists, spanning ‘Poetry & Drama > Shakespeare, William’ but also – less predictably – ‘Media & Communication Industries > Press & Journalism’ and ‘Literary Theory & Movements’.

It seems to me that working collaboratively and across traditional disciplines will necessarily produce publications and other outputs that resist standard categories. Part of their role is to unsettle modes of thinking in silos, especially in relation to subjects long considered ‘high’ or ‘low’ culture and therefore mutually exclusive. I therefore take this comment as a ringing endorsement of our interdisciplinary approach and its published product.

*

Images Courtesy of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust. Information about objects in the SBT’s collections, with downloadable images, is available online via the SBT’s new integrated catalogue: http://collections.shakespeare.org.uk/