We’re delighted to announce that our co-authored book, A Day at Home in Early Modern England: material culture and domestic life 1500-1700 will be published by Yale University Press on 3 October.

On the front cover is a drawing from the Trevelyon Miscellany of 1608 in the Folger Shakespeare Library.

This domestic scene is used by Trevelyon to illustrate ‘the malice of a woman’. A scolding wife stands over her subservient husband who is winding yarn while, in the background, a shocked neighbour walks in to discover such disorderly housekeeping. The image represents our book’s concern with gendered work within the household, and the social significance and scrutiny of domestic matters at the middling level.

The remarkable openness of the domestic to the community is made plain in the many court depositions we examine in the book. An ecclesiastical court case of c.1619 from Bishampton, a village near Worcester, did not end up in the book but it offers a fascinating window onto early modern domestic life (quite literally) and serves as a little taster of A Day at Home.

The case, Smith v Fareley, concerns two women and is prompted by a pew dispute – fascinating on its own terms – but as background to this dispute we learn about a slander.¹ Where this insult takes place provides a good deal of information about the visibility (and aural porosity) of domestic life.

The depositions first describe an incident whereby on a Sunday around Whitsun 1619 during evening prayer one Ann Fareley took it upon herself to sit in a seat ‘in which Jane Smith… had sat for many years’. Smith’s seat ‘was her right by her house’ and, as one deponent placed it ‘the uppermost seat except one, in the row in which the women sit’. This position close to the front of the church suggests that Jane Smith was a housewife of some status in the community of Bishopton, occupying the seat by right of her house, which before her was attached ‘to the occupier of the house in which she lives’. Ann’s lower status reflects that of her husband, who is not a settled householder, but lives with his father.² At the time of the tussle over the seat, Jane was pregnant. According to Dorothy Hay, a 40 year old farmer’s wife who occupied a pew near to Jane Smith’s, when Jane tried to enter her seat Ann wouldn’t let her, ‘putting her foot up on the opposite bench’. After the service Jane showed some neighbours the inward side of her thigh ‘which appeared to be of a black or blwysh color’ caused apparently by ‘the violent and forcible thrusting of Ann forth of her pewe’.

Further depositions suggest this incident was part of a longer campaign of abuse. Several deponents described how a few months earlier, on the Tuesday before Palm Sunday, Ann Fareley had insulted Jane Smith in her home. According to Jane’s 19 year old servant, Joanna, ‘her master and dame being at supper, The defendant then standing at the plaintiffes window overhearing there[their] speeches in very violent and malicious manner said unto the plaintiff Come up yow Lyeing whore, yow mangy whore sayeing that is one of thy old Lyes often tymes calling her the plaintiff whore wi[th] ill addicions which wordes were spoken at the wyndow of the plaintiffes dwelling howse in Bishampton in the hearing of this deponent[,] Edward Stevens and John Gawe’. Edward Stevens was also in the Smith’s service and in his deposition agreed that Ann was ‘then standing on the owtside [of] the wyndow’.

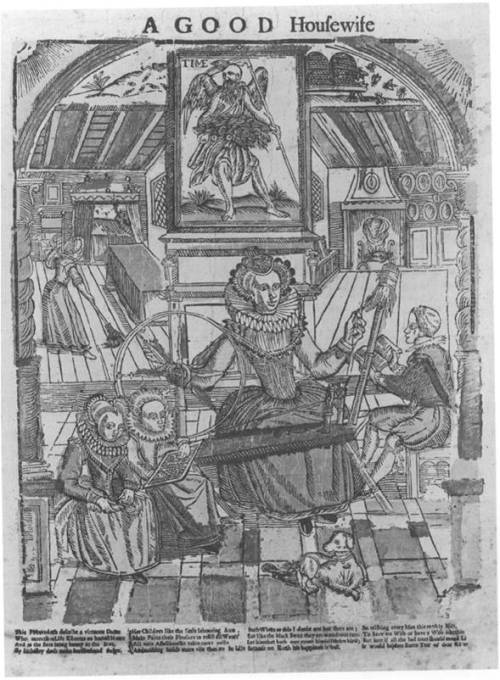

Woodcut included in ballad, ‘A good throw for three Maiden-heads’, London, 1629.

John Gawe[actually Gaywood], a farmer, described what he saw of this incident as, on his way home, he ‘passed close by the plaintiffes husbandes howse … And as he was passing by he sawe Anne Fareley the defendant in the plaintiffes yeard nere to the wyndow of his [Smith’s] dwelling howse At which tyme this deponent heard the said defendant call Jane Smith divers and sundry tymes whore very maliciously And this deponent reproving her for so calling her in her owne yeard she grewe very impacient with this deponent’.

This case reveals a great deal, then, about housing conditions within this village setting. The Smiths must have occupied one of the more substantial yeomen houses within this village according to their customary seat in church and because they were of a status to employ two servants (at least). Yet access to this property was evidently quite open; John Gaywood passed close by his neighbour’s house on his route home from work and could see into his yard where Ann Fareley was standing outside a window. That window obviously gave onto the Smith’s hall or parlour where they were having supper and the ‘speeches’ between Smith and his wife as overheard by Ann seemingly prompted her malicious words. That window was presumably fully open, if glazed, but was more likely unglazed with shutters. Pendean farmhouse from Midhurst re-erected at the Weald & Downland museum is an example of a farmhouse built on a modern house plan with integrated chimneystack c.1600 but with unglazed windows.

Pendean Farmhouse from Midhurst, Sussex, built 1609 now re-erected at the Weald Downland Museum to reflect its original form, including unglazed windows.

Why Ann was standing there within the yard of Smith’s house is not explained. It is possible she was involved in day work for the Smiths; this might explain why she had a particular grievance against Jane as her mistress. But perhaps no explanation for Ann’s seemingly intrusive presence is needed since such scrutiny of the domestic affairs of others was expected, indeed encouraged, during this period.³ The rich painted wall decoration of halls and parlours – a common feature of interiors in the first half of the 17th century – could, therefore, have been intended to impress passers by as much as social peers.

How the Smiths’ dining space was decorated is not known but if it resembled decoration elsewhere then Ann might have been gazing in upon a space adorned with phrases in black letter text such as:

‘to his neighbour doth none ill in body, goods or name / Nor willingly doth move false tales, which might empair the same / That in his heart regardeth not, malicious wicked men / But those that love and feare the Lord, he maketh much of them.’ [From The Whole Booke of Psalmes collected into English Meter, first published 1562]

One of the black letter texts based on a selection of psalms and proverbs in the painted decoration of a first floor room at 1 Church Street, Ledbury.

Such texts from Psalms and Proverbs were common in the painted decoration of the best rooms in middling houses. Despite Ann’s unseemly disruption of their supper, the Smiths could take consolation from their superior social and moral status as householders.

Watch this space for more on domestic wall paintings, coming soon…

¹ Worcestershire Archive and Archaeology Service, Worcester, Deposition Books, 794.052, vols 6-8 (1612-29).

² On the relationship between social status and church seating see C. Marsh, ‘Order and Place in England, 1580-1640: The View from the Pew’, Journal of British Studies 44.1 (2005), pp.3-26. On the gendered significance of church seating see Amanda Flather, Gender and Space in Early Modern England (Boydell & Brewer, 2007).

³ Lena Cowen Orlin, Locating Privacy in Tudor London (Oxford University Press, 2007);